An interview from the Archives of The Bloomsbury Review

From Volume 1/Issue 1—November/December 1980

Horned Toads, Hawks, Coyotes, Rattlesnakes,

and Other Innocent Creatures

An Interview With Edward Abbey

by Dave Solheim and Rob Levin

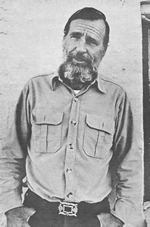

Probably more than any other living writer, Edward Abbey is the spokesperson for the American West. He has published six novels (the most recent of which, Good News, is reviewed in this issue) and eight books of nonfiction essays and travelogues. Although he is one of the leading spokespersons for the preservation of wilderness, he defies labels. He believes in the wilderness first of all for its own sake, and secondly because it allows human beings to have the feelings of danger and freedom that are too often removed from modern life. He is not the new Thoreau of anything, but will wear, if somewhat uncomfortably, the labels of anarchist and wild preservationist. But don’t let that fool you. Abbey is as diverse and slippery as the slickrock country he writes about and as predictable as a flashflood.

Abbey lives at home in the desert southwest near Tucson with his wife and two dogs, Bones and Elly. The dogs are like him in that they prefer to spend the day wandering the desert. His clothing frequently looks government issue, maybe left over from his previous work as a park ranger, forest ranger, and fire lookout. He wears combat boots made in Taiwan. “They feel good; they wear well.” Though he may at first appear as a slightly disheveled Smokey the Bear, Abbey is far from G.I. He is consistently radical, but relishes the complications and contradictions of being human.

The Bloomsbury Review: In some of your novels, major characters seem to be killed only to return to life later: Jack Burns in The Brave Cowboy and in Good News, and George Hayduke in The Monkey Wrench Gang. Are you too attached to your characters to finally kill them off, or is there more justification for these resurrections than I have noticed?

Edward Abbey: I believe in happy endings, and furthermore, I do not understand my own books, very well, anyway. Jack Burns also appears in The Monkey Wrench Gang. I do like to keep my endings open. The first edition of The Brave Cowboy was too closed, but I corrected that in later editions.

TBR: Can your readers expect to hear more of Hayduke or Burns in future novels?

EA: Very likely.

TBR: Maybe the middle of Jack Burns’ life?

EA: That’s a good idea.

TBR: George Hayduke seems to be a sociopath. He wants to drive his jeep and throw his empty beer cans wherever he wants to. Is even the West big enough for more than one or two Haydukes? Do you have any reservations about presenting such a character in a favorable light?

EA: Hayduke is Hayduke. I do not feel responsible for his behavior.

TBR: The Monkey Wrench Gang suggests that old four-wheel drives are good and that new ones deserve to have boulders dropped on them; that it’s OK to use a chain saw on billboards, but not on trees. Is that important to the novel?

EA: I think that I shall never see a billboard lovely as a tree.

TBR: At the end of Desert Solitaire you suggest that both the city and the wilderness are necessary for modern human existence. Good News, your latest novel, opens presenting “the oldest civil war, that between the city and the country.” Does this show a change in your thinking or did your idea of balance include the tension of conflict or even war?

EA: All of the above. I’d like to live fairly near a city, but I don’t have any desire to live in a city. Where I’m at now suits me fine. If it’d stay this way, I could live here the rest of my life. But very likely, this will all be built up in a few years.

I’d like to live 50 or 60 miles out in the country from a city like Tucson or Santa Fe. Or Salt Lake. Or 500 miles out in the country and get an airplane and a pilot’s license. As I’ve said before, I’m not a recluse or a hermit. I like some social life. I’d like to have the best of both worlds. The wilderness and urban civilization.

TBR: You are noted for the political activist stance of your novels. Do you have to control your characters to serve your political ends?

EA: I try to control my characters, but they almost always get out of hand. They like to go their own ways.

TBR: I have a half-baked theory that one distinguishing feature of western literature is that the landscape is an active character; a participant in the events of a novel; that the landscape acts on, and interacts with, the human characters. In Good News landscape is replaced by a burned-out cityscape. Is that important?

EA: I certainly agree that the landscape is a major character in most western novels, and probably should be. But I also believe that the land acts upon and shapes human beings everywhere, eastern as well as western, city as well as country.

TBR: I guess that takes care of my theory.

EA: I do think you’re right. The land, the earth of the American West, is unique. It acts in ways that are hard to describe.

TBR: In your introduction to Abbey’s Road, you mention a number of writers whom you respect. You seem to be the only western writer I’m familiar with (except for Tom Robbins, whom you don’t mention and who might not be a western writer) who has an urbane, ironic wit in your work. Would you comment on that, or correct me where I’m wrong?

EA: Well, I’m not a Tom Robbins fan. I like his first book, Another Roadside Attraction. I tried to read Even Cowgirls Get the Bluesbut could not get through it. It’s just too cutesy-pie for me. I regard him as a kind of shampoo artist or a cotton-candy vendor. Writers whom I really admire who live in, or write about the West are: William Eastlake, Wallace Stegner, Tom McGuane, Wright Morris, Larry McMurtry, and I think all of them have plenty of wit and irony.

TBR: Would you discuss a few of your favorite writers, both classic and contemporary, and tell why they are your favorites?

EA: Well, I suppose it’s much more interesting, isn’t it, opinions on contemporary writers. We all admire Shakespeare and Tolstoy, or most of us do. There’s nothing much new to say about them. Well, I like McGuane and Pynchon. Oh, Christ, I’m not much of a critic, I’m not very good at analyzing things. I think it’s probably a matter of style. I just admire very much the way they write, the way they handle the language. Have you read Pynchon? Gravity’s Rainbow? It’s almost incomprehensible to me. I find great difficulty in what the hell he’s saying as I go along, but I read it anyway. I enjoy it. I find it fascinating, even though it’s so complex and dense and obscure and mysterious that I don’t know quite what he’s saying.

McGuane is a very clear writer, although he has opaque paragraphs here and there. His writing always has a kind of bloodchilling nihilism to it that I can’t always find appealing. But it’s interesting, it’s powerful.

Another contemporary writer I admire would be William Eastlake, also a friend of mine. He lives down in Bisbee (a small town about 90 miles southeast of Tucson, on the border). He wrote some novels about life in New Mexico. He wasn’t very serious about it. He wrote three novels about contemporary New Mexico. And they are marvelous novels. Indians and cowboys and jazz musicians and tourists and ranchers and written in a very witty, ironic style. Eastlake is also a master of the sentence and paragraph.

And there’s Alan Harrington. I might as well put in another plug for a writer and friend who lives out here in Tucson. He, I think, is a great essayist. He wrote the book The Immortalist. Immortalist is not a novel. It’s a 300-page essay on the subject of death and immortality—the very things we were told to avoid as journalism students. It’s a very interesting book, full of interesting ideas. And Alan has also written some good novels, mostly about New York life. He was a New Yorker for about 20 years. He moved out here about 10 years ago. And he just finished a novel a few days ago called The White Rainbow, which is about Mexico and the old Aztec traditions, human sacrifice—kind of a morbid book, but very interesting. I’ve read parts of it, and he’s read parts of it to me.

I like Nabokov quite a lot. I was shocked that he did not get the Nobel Prize. I admire him chiefly as a stylist, a master of language. He’s a Russian who can write English much better than many of us Americans.

B. Traven is another literary hero of mine. He’s not such a well-known American writer, if he was American. His whole life was sort of a mystery. He may have been born in Germany. He lived most of his life in Mexico. He wrote The Treasure of Sierra Madre, which became the famous movie. But he wrote abut half-a-dozen other novels that are just as good. His best was one called The Death Ship, about a sailor’s life in the merchant marines in the 1920s.

Well, I could go on and on. There are many living writers I admire. I think there’s a helluva lot of challenge here in the United States. No writer that I would call great. I don’t think we have another Faulkner among us. But who knows. Pynchon is still fairly young, and so is McGuane. I think they’re both in their thirties.

TBR: At least for the last few years you have lived in the rural Southwest. How important is that location for your writing? Would you be as significant a writer as you are now if you had continued to live in New Jersey or New York?

EA: That’s a good way to phrase it. I sometimes suspect I might have been a better writer if I’d stayed back East; it’s a lot easier to sit indoors there. But I don’t think I’d be so happy a man. The Southwest is definitely my home, and I think it always will be. At least I hope so. I’ve lived here a long time. Since 1947 except for a year in Europe and one year in New York. So I’ve lived most of my life in the Southwest.

TBR: Is there one state or town that you consider home? You’ve said that you were going to leave here when your wife finished college. You’ve lived many other places. Does it make any difference so long as it’s in the Southwest?

EA: I call a very large area home. Parts of Mexico, Baja California, all the way up into parts of Wyoming. I don’t think it matters very much. I really do regard the whole Southwest as my home. I’m perfectly happy to live anywhere in Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, Nevada. I like the desert; I like the hot, dry climate. I hate to be cold and wet, especially both at the same time.

TBR: You have said some harsh things about the New York publishing establishment. Your books have been published by large houses and re-issued by the University of New Mexico Press. What role do you see that university presses, small presses, and non-commercial presses have in the world of publishing and conglomerates?

EA: I’m all for them. I think there will always be a role for the small presses and the university presses. They serve as outlets for scholarly work and for new and experimental fiction, and writing by new and unknown authors that the national publishers will not take a chance on. I think both of these presses are useful and necessary and always have been in American literature. You may recall that Thoreau paid for publication of his first book of which he sold 200 copies out of a printing of 2,000. The advantage of big publishers is the large audience. A writer wants to be read by as many people as possible.

TBR: At this stage of your career, you probably have no need for it, but did you ever want to work in a community of writers? What do you think about university writing programs?

EA: First of all, I don’t have a career, only a life. Writing books is a passion. But it’s only one of several passions. No, I would not want to work in a community of writers. Trying to live with one writer—myself—is difficult enough. Many other writers have influenced me, certainly. But they’re not to blame for anything. As for college writing programs, I doubt if they do any harm. If a student is interested in writing, or wants to become a writer, he probably should take a writing class. I took one or two when I was a student. They might teach you something, but most of all they give you pressure to write. That’s the hardest thing about writing--to get started, to put the first things down on a page.

TBR: What makes you write now? When you’ve been loafing, hiking, hanging out for a year or so do you make notes on things? When do you decide you can’t put it off any longer? Does the pressure to write keep building?

EA: I do make notes. I have such a bad memory that I have to, or I’d forget everything. There are two forms of pressure. One is psychological and the other is financial. I make my living by writing--mostly. I’ve also made a partial living from being a fire lookout. You know, the psychological pressure builds up. If I’m not writing, I begin to feel guilty, useless. Sloth and bloat set in. I get itchy. I’m too much of a Puritan to be a good loafer, I guess. And also, I take assignments, do magazine articles, have to meet deadlines …

TBR: In Abbey’s Road you claim to wear a tie when you write. You aren’t wearing one now.

EA: I have worn a tie. I’ll probably die in one.

TBR: Several of your characters have spent time in jail. Have you?

EA: Yes, I have been in jail a few times. Once for vagrancy, once for public drunkenness, once for reckless driving—what the police called “negligent driving”—rather than trivial offenses. I’m not very proud of them. But I think it’s important for a writer to spend at least one night in jail, maybe even more important for lawyers and judges. I have not been in jail for refusing to pay taxes. I tried to not pay taxes in the late sixties, but they just went to my employer at the time and garnished my wages.

TBR: Violence is in most of your writing. Has violence directly affected you in any way?

EA: As for violence, I’m against it for I am a practical coward. However, violence is an integral part of the modern world, modern civilization, and I assume that someday I may have to face it. So I load my own ammo. There are a few things worth killing for. Not many, but a few.

TBR: Your master’s thesis in philosophy was a study of the ethics of violence. I understand you were frustrated by restraints placed on it by the faculty committee?

EA: Yes, I wanted to write a book that I was going to call the General Theory of Anarchism. Fortunately, the thesis committee was not interested in that kind of tome, or I’d still be working on that first treatise.

TBR: Although you’ve been reluctant to talk about it, when you were the editor of The Thunderbird , the student literary magazine at the University of New Mexico, the university president suspended its publication for a year.

EA: Well, in my case it was kind of a showoff stunt. It was sort of silly, but what I did was put a quote on the cover of this magazine that said: “Mankind will never be free until the last king is strangled by the entrails of the last priest.” And I attributed that to Louisa May Alcott. False, of course. It was some Frenchman. Diderot, I believe. And of course, I got the Catholics in an uproar about that. I don’t blame them. It was kind of a stupid thing to do. I was just trying to attract attention.

TBR: You said you were a practical coward?

EA: Well, I try to avoid direct physical violence if possible. I’ve never been in a barroom fight. I’ve been in plenty of barrooms. Some close calls, but usually, always, I’ve been able to talk my way out of it. I haven’t been in a fight since about the fourth grade when I beat up my best friend, the only guy in the class I could lick.

TBR: How do you feel about your work being the subject of academic study? Would you prefer a barroom discussion of your books to a classroom discussion?

EA: I don’t care where my books are read or by whom. I’m happy to be read by anybody, anywhere. I’ve no objections to people talking about them in a classroom or in a barroom, as long as it’s done voluntarily by willing victims.

TBR: They could be required reading.

EA: Well, no one is required to go to college. At least not yet.

TBR: You aren’t worried about what academic people might do to your work?

EA: No. I don’t think about it. Let them do their work. I’ll do mine.

TBR: After people read your books, how would you like them to think of you, or do you care?

EA: All writers need love, appreciation. I think I write mainly to please myself, because that’s the easiest way for me to write. I don’t have any analytical or critical ability. I cannot design a book very well. I write rapidly, spontaneously, out of the belly and bowels. And usually from a very personal point of view.

Most of my work doesn’t get very good reviews, especially back East. I’ve got this grudge against New York’s book reviewers. I don’t think they take me seriously. All western writers feel that way, though. All of us who live out here and write out here.

As I said, we all want to be loved, appreciated. Fame. The desire for fame is certainly one of the motives for writing. I suppose there’s a danger in too much fame, too much money. I guess that could spoil a writer. I haven’t had an opportunity to deal with that yet. But I’m willing to take the chance.

I think all writers are egotists. I wasn’t much good at athletics. I couldn’t even make the high school basketball team. Oh, I suppose it’s true that artistic ability in writing is compensation for failure in some other line. But I wouldn’t make much of that.

I think writers have it pretty good. Especially anybody that can make a living by writing, which I’ve been able to do for the last 10 years. I’m a pretty lucky person, which doesn’t necessarily mean I’ll be happy.

TBR: You present yourself and seem to think of yourself as a novelist. Suppose, for the sake of argument, that you are considered to be more important as an essayist, or worse yet, a nature writer. How would that affect you and your writing?

EA: I go my own way, do the best I can, writing mainly to please myself. But it is on the assumption that there is an audience out there somewhere, made up of people pretty much like myself, or at least people who think and feel like me. So far that approach seems to work. I don’t know whether I’m primarily a novelist or essayist or something in between. I don’t really worry about that.

TBR: What would you say are your strengths or weaknesses as a writer?

EA: I guess I’d have to divide fiction from nonfiction to answer that question. As an essayist—I like to call myself an essayist, it sounds good, instead of a journalist. I’ve said some nasty things about journalism, journalists. But I’m a journalist myself half the time, when I do my magazine writing.

TBR: You have written some less-than-complimentary things about journalists.

EA: Yeah, that was meant to be a put-on. I didn’t think anybody would take that seriously. I was once editor of a small-town weekly. For six months I was editor of the Taos weekly newspaper. It went out of business, and I lost my job. I took journalism in high school, flunked it twice. Same course, flunked it twice. I just couldn’t get the facts straight. I had a hard time making the news fit the page, doing the layouts. So all those nasty remarks I made about journalists were meant to be, hopefully, a put-on. But I would like to call myself an essayist. But anyway, getting to the weaknesses …

On nonfiction, and I’ve been criticized for this, I tend to be self-indulgent. I ramble on and on. I write too much about myself. Sometimes it works pretty well, but it can be overdone. After awhile, the reader really gets tired of hearing about the writer’s personal problems and opinions. He’d like a more objective point of view, a description of what’s going on out there.

In fiction, I’ve published six novels now, and I wrote a couple of more that were unpublished, rejected. And I’ve got two or three more in my head that I want to write. My main difficulty in fiction, especially in novel forms, is plotting: How to arrange the material in the most effective way. I just don’t understand how you construct a plot. I generally follow the obvious, most simple way. Beginning at the beginning, follow a linear chronology. I tried writing short stories long, long ago. I found them even more difficult. There you really have to exercise discipline, know what you’re doing. I’m not any good at that. For me, the novel is easier to write than the short story. You can get away with more looseness and carelessness. I can’t say anymore. I don’t like to talk about my weaknesses.

TBR: You already have. But what about your strengths?

EA: Oh, hell, I can’t analyze my own work. I really just write to suit myself. I work very fast, in spasms and in spurts and loaf a lot between projects, books or articles. I think I write fast, but carelessly, but always pretty damn spontaneously, which may be both a strength and a weakness.

TBR: I’ve heard that you are working on an autobiographical novel. If that is so, is it from any attempt to merge the fiction and nonfiction writing you have done?

EA: No. I’ve got some good stories left, and I want to write about one good, fat book and then perhaps I’ll resign from my author business and do something different. I want to build a house. A stone house. Maybe an adobe houseboat. Raise my children, blow up something. I don’t know.

TBR: Your novels might be seen to suggest that all attempts to make a living in the West are destructive. Are there ways to live here that don’t destroy the land or the humanity of the people?

EA: I believe that farming, ranching, mining, logging are all legitimate, honorable, useful, and necessary enterprises. I respect and admire those who carry on these occupations. Especially those who do it in a way that treats the earth with love, and the rights of our posterity with respect. The problem, where things go wrong, is in scale, size, number. The carnage that we’re doing to the American West, the planet as a whole, results, I think, mainly from too many people demanding more from the land than the land can sustain.

TBR: In Good News a minor character, Glenn, is a piano player who attempts to return to being a composer, a musician, even though he has no audience. Could he be seen as a metaphor for the role of the artist in the West?

EA: No. I don’t think so. That character is just being true to his way of life. He will go on making music even for an audience of one—himself. I don’t think he’s a metaphor for anything more.

TBR: Another character, Sam Banyaca, is a Zuni who presents himself as a magician, able only to do sleight of hand, yet at several key points in the novel, he performs with the real power of a shaman. Are you presenting Indian traditions of mystic power as viable for non-Indians in the modern, technological world?

EA: I’d rather not explain that. There is an explanation for it in the novel that is bigger than you suggest, but I don’t want to try to explain it. Yes, I do think Indian beliefs, traditions, and customs have much to teach us. We have much to learn.

TBR: Is there a difference between Sam and, say, Carlos Castaneda?

EA: I’ve said about all I want to say about Castaneda. Sam is a trickster and occupies a special position. There is a narrow line between magic tricks and power. A difference that won’t quite fit in words.

TBR: Do you consider yourself a practical man or a romantic man?

EA: I’m a practical romantic. I worry about making a living, raising my three children, getting my wife through college, paying my bills. I’ve got myself trapped in the same sort of mortgage situation as most other people around. But I have to make a living one way or the other. To that extent I’m a practical man.

TBR: To what extent are you a romantic?

EA: Well, I love to be in love … with many things. I tell ya, these are rather probing questions you’re getting at here. That’s an interesting question, though. I do consider myself a romantic. Partially, I suppose, because I’m an idealist. I still think it’s possible to find some better way to live, both as an individual and as a society. And I have the usual romantic ills—thinking things must be more beautiful beyond the next range of hills. I’ve been fascinated by the mysterious and unknown. Those are romantic traits.

TBR: What is the worst possible future you see for the American West?

EA: The worst possible future for the American West is already here. At least I hope it is the worst. I am an optimist. I believe that the industrial, military state will eventually collapse or destroy itself.

The horned toads, the hawks, and the coyotes and the rattlesnakes and other innocent creatures I hope will survive and carry on, and yes, probably a few humans with them, or at least I hope so. I think the human race will get one more chance. I’m not sure we deserve it, but I hope we get it anyway.

I look forward to the day when gasoline becomes so expensive and motor vehicles become so expensive that we all have to go back to horses and walking. I’m willing to give up my truck … if everybody else does. All right. Enough of that. You want to go for a walk?

[1980] Dave Solheim is a graduate student in creative writing at the University of Denver; Rob Levin is a reporter for The Arizona Daily Star. This composite interview was conducted by Dave Solheim and Rob Levin and edited by Tom Auer.

[2011] Dave Solheim is professor of English at Dickinson State University in North Dakota. His most recent book is The Landscape Listens: Poems (Buffalo Commons Press); he is also the author of West River: 100 Poems. Rob Levin is president and editor of Bookhouse Group, Inc., an Atlanta-based book development and publishing company.